Malsawmdawngliani, a nurse who has served over 20 years at the Hnahlan Primary Health Centre (PHC) in Champhai district, Mizoram, remembers an incident from nearly six years ago that haunts her to this day. On 14 September 2019, a baby girl with pneumonia and serious breathing difficulties was brought to the health centre. She desperately needed oxygen, but a long power cut rendered the oxygen concentrator unusable. The backup diesel generator was also out of commission.

Speaking to The Better India, Malsawmdawngliani recalls, “Due to the power cut, we couldn’t administer oxygen to her. I can’t forget seeing her health deteriorate as we watched helplessly. The baby sadly died, and till this day, I cannot forget the pain I felt that day.”

In Mizoram, a state characterised by lush rolling hills and stunning green valleys, such frequent power disruptions were, until recently, a common occurrence, severely impacting healthcare services in PHCs and other last-mile health centres.

As Dr Lalnuntluangi Chawngthu, Assistant Director, Directorate of Health Services, Government of Mizoram, notes, “While many health centres in Mizoram are connected to the electricity grid and generally receive a stable power supply, a significant number of PHCs and sub-centres in remote and hilly areas frequently face disruptions. These interruptions are largely due to environmental and geographic challenges unique to the region — such as heavy rainfall, landslides, and cyclonic storms — that damage power lines or restrict repair access. In such remote terrains, even minor infrastructure breakdowns can lead to prolonged outages, affecting the regular functioning of essential services like health care.”

Dr Lalnuntluangi also recalls an incident from a decade ago when a similar outage disrupted critical vaccinations. At the time, she was posted as a young doctor at the Bunghmun PHC in Lunglei district, Mizoram.

“During the monsoon season, relentless rains triggered massive landslides, completely cutting off the area. A seven-day power outage followed, which led to many vaccines getting spoiled. As a result, there was a delay of nearly two weeks in vaccinating children,” she recalls.

Table of Contents

A solar solution for last-mile healthcare

To address these concerns, the Mizoram government collaborated with SELCO Foundation, a non-profit operating in seven Northeastern States, to empower communities by improving access to last-mile healthcare delivery and to “achieve blanket solar electrification of health centres across the state” in 2023, according to Dr Lalnuntluangi.

This initiative is part of SELCO Foundation’s larger programme, Energy for Health (E4H), which seeks to harness renewable energy to transform last-mile health centres in Northeast India. The programme in Mizoram was supported by the IKEA Foundation, the Waverly Street Foundation, the Ashraya Hastha Trust, and LIC Housing Finance.

Since the inception of this programme in Mizoram, Dr Lalnuntluangi claims that more than 300 of the 443 sub-centres in the state have been solar-powered.

“The collaboration has reached health centres in all 11 districts, significantly improving energy access in hundreds of villages. In 2025, SELCO Foundation is scheduled to solar-power 98 more sub-centres, focusing on the remaining few in ultra-remote or previously inaccessible locations. This expansion aims to achieve 100 percent energy coverage for rural health infrastructure in Mizoram, setting a precedent for decentralised energy-based health system resilience,” she adds.

Solarising 300+ rural health centres

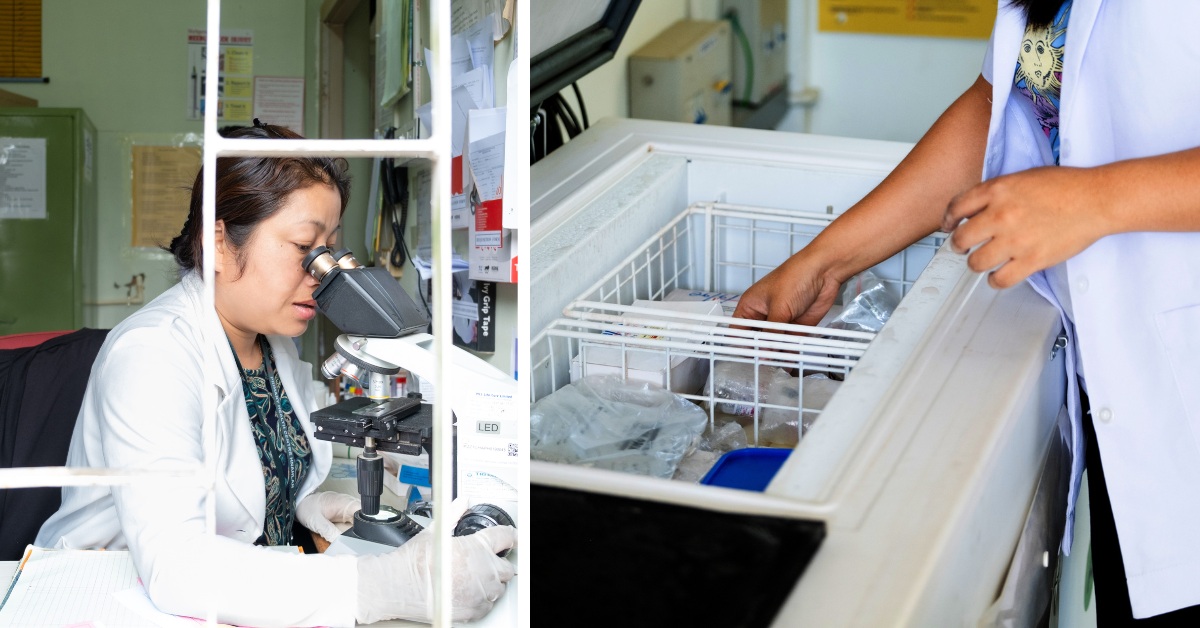

A core component of the E4H programme is their Decentralised Renewable Energy (DRE) technology — solar panels, batteries, earthing cables, and charge controllers — and the operations and maintenance processes that enables health centres to not only become energy sufficient, but also enables the state to become climate resilient, and more productive in delivering affordable healthcare.

Elaborating further, Huda Jaffer, the Director of SELCO Foundation, writes in Following the Sun, a book documenting this collaboration:

Our DRE system batteries come with a warranty of five years as mandated by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE); if maintained very well, they run for about eight to ten years. Panels also come with a similar warranty, but they typically last about 20–25 years. Hence, capacity building for maintenance is a core focus area. It includes pre-installation, installation, and post-installation training for local enterprises and technicians.

We cannot expect anyone to provide this service for free. So, we prioritise local enterprises with a good service network to install the systems, and the payment comes, and this is a systemic innovation, from untied funds with local Rogi Kalyan Samitis. These are patient welfare committees enabled by the NHM (National Health Mission) that act as trustees for hospitals and health centres. They are free to prescribe, generate, and use their funds as per their judgment for the smooth functioning and maintenance of the services.

E4H DRE systems have a standard built-in autonomy of two to three days, but if we implement them in an area with very heavy rainfall or high cloud cover, we extend it to five to six days. If our systems can function well in Meghalaya’s Cherrapunji (Sohra), one of the world’s wettest places, then they can work anywhere. We have collaborated with the state governments to ensure that when they procure new equipment, like baby warmers, oxygen concentrators, and freezers, they acquire the most energy-efficient appliances available. This could potentially result in reduction in energy requirement by 60% to 80%.

Before installing the systems, however, it’s imperative that the staff at these health centres fully understand the system and its benefits. What follows is a training process for the staff to operate and maintain the system so that they can take ownership of it down the line.

For example, if a panel breaks or a charge controller stops working, the health centre staff can determine how to fix the issue without delay. This degree of engagement is necessary for the sustainability of E4H. Having said that, systems and processes are not enough.

Investing in local champions — whether a doctor, teacher, village elder, farmer, night nurse, district health officer, or health secretary — is also key. When recognition of the true value of E4H occurs, these individuals become genuinely interested and invested in the programme.

Training locals to keep the lights on

Medalthanga, a science teacher in Zokhawthar, a town along the India-Myanmar border in

Champhai district and a member of the Young Mizo Association — a deeply influential civil society organisation in the state — is one such local champion of the programme.

Residing in Zokhawthar with his family, he notes how public transport is non-existent and power supply is extremely unreliable. However, he is thankful that the sub-centre now benefits from a solar power system, which “has made it possible for the staff to offer health services 24/7.” He adds, “The outpatient department is busy during the day; vaccination drives are conducted once a month, and emergency and delivery cases are common at night.”

Coming back to the training process, Dr Lalnuntluangi says, “To ensure long-term functionality, a structured operation and maintenance training program was designed for 883 healthcare workers across 443 health centres (69 PHCs, 374 sub-centres) in 11 districts.”

The training module essentially involves teaching staff how to operate and troubleshoot common issues in solar equipment. They are also taught the use of the Saur-e-Mitra app, which helps PHC staff monitor solar energy use in real time. The app allows them to track system performance, report issues quickly and manage basic maintenance work.

“All 443 health centres across Mizoram have been covered through 49 training sessions, conducted by 7 trained master trainers,” claims Dr Lalnuntluangi.

She adds, “To ensure community involvement post-installation, SELCO has actively engaged the Young Mizo Association and JAS (Jan Arogya Samiti) committees to build awareness and responsibility. Local electricians and youth have been trained in basic solar maintenance. These trained individuals provide first-response support and routine servicing, creating a decentralised maintenance model that empowers the village and builds ownership.”

None of this progress would have been possible without the active participation of the Mizoram government. Rachita Misra, Associate Director at SELCO Foundation, notes how state officials supported the vision even before the programme took off.

“State officials did their due diligence and understood not just the solar technology but also the intervention that we were proposing — using solar energy to decentralise health services. They had an active understanding of the efforts that they needed to take towards that goal. The approach has always been that it’s not just about solarisation. It’s really about how the health department takes leadership in asking, ‘How do we make our public health system more resilient and more focused towards the people who need it the most so that we reduce transaction costs, decentralise health services and deliver them with no barriers?’” she says.

From dark clinics to solar-powered care

Ultimately, the real success of the programme lies with the communities that benefit. As Dr Harish Hande, CEO of SELCO Foundation, notes in Following the Sun, the decentralised energy solutions developed for these sub-centres “enable healthcare to be accessible to the poor, near their homes, in the most affordable manner from their perspective.”

Take the PHC in Hnahlan, a town bordering Myanmar, for example, where nurse Malsawmdawngliani works. This health centre provides care for approximately 3,500 residents from the nearby villages. Most patients coming to this border trade town are small farmers and daily wagers who cannot afford private healthcare.

Although the primary purpose of the PHC is to treat common illnesses, it also provides long-term care for poor patients. This situation increases the workload for the entire staff, who use all available space creatively. The PHC has 10 beds, including two reserved for childbirth, but additional beds have been set up in the corridors to accommodate up to 25 patients.

Dr Vanlalpeka Pachauau, who has worked at the centre since February 2023, recalls the challenges before the new DRE system was installed. “Initially, we had one small diesel generator backup. We had a solar energy system, but it was rundown due to a lack of maintenance. This was particularly challenging for patients needing oxygen concentrators and new mothers requiring infant warmers for their newborns. Operating the PHC with regular power cuts was a real challenge.”

Since the installation of the DRE system, Dr Vanlalpeka notes that “things have significantly improved in terms of our ability to better serve our patients and the community.”

“For example, about a week ago, there was a power cut in our village that lasted for two days. Patients under home-based care who ran out of oxygen came to our PHC in droves because we had regular power and could operate our oxygen concentrators to help them. Even though technically we had just one out-patient, our PHC was filled with people needing oxygen. We have a generator backup too and use that along with our solar backup,” he shares.

A couple of months ago, during a visit to Ajasora village in Lawngtlai district — a remote settlement serving over 7,000 people across 11 surrounding villages — Dr Lalnuntluangi’s colleagues witnessed firsthand the programme’s impact.

“Until December 2023, the local health centre operated with an irregular power supply. A local health worker, Krishna Devy Chakma, shared how critical procedures, such as nighttime deliveries, were performed using mobile flashlights or candles, increasing the risk for both mother and child. Since the installation of the solar energy system, the transformation has been remarkable,” she notes.

She goes on to elaborate on how labour rooms at the health centre are now equipped with energy-efficient fans and lights, solar-powered baby warmers and medical lights (enabling safer childbirth), and cold chain systems (like the ice-lined refrigerator) storing essential vaccines and life-saving medication.

These improvements, she says, go far beyond equipment upgrades.

As Dr Lalnuntluangi puts it, “Uninterrupted power is critical — not just for medical equipment, but for restoring dignity, safety, and confidence in rural health services.”

Edited by Khushi Arora

Source Link: thebetterindia.com

Source: thebetterindia.com

Via: thebetterindia.com